- News

- City News

- srinagar News

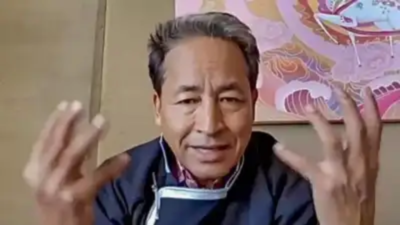

- Environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk blames faulty govt policies

Trending

Environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk blames faulty govt policies

SRINAGAR: Ladakh UT authorities have formed a committee to map out the reasons behind “diminishing interest” in rearing of pashmina goats, whose wool is used to weave the famed pashmina shawls.

The panel has been asked to submit its report within 10 days and suggest an effective strategy to retain people, especially youths, in “traditional livelihoods. But environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk attributes the pashmina decline to decades of misplaced development policies in the region.

Changthang region of Ladakh, around 230km from Leh, is home to Changra goats or pashmina goats, whose wool is said to be 6 to 10 times finer than human hair and eight times warmer than sheep wool.

The region -- the highest permanently inhabited plateau in the world -- is witnessing shepherds giving up Pashmina rearing, a trend that has alarmed authorities. For centuries, the hardy nomadic shepherds have roamed Changthang, herding yak, sheep, and goats. But now, pashmina rearing is becoming difficult and no longer provides a sustainable livelihood, leading many to move towards tourism and labour-related vocations.

Ladakh principal secretary (commerce) Sanjeev Khirwar called it a critical issue. “There is an urgent need to improve the remuneration and economic conditions of the farmers and herders. Unless these communities are provided with sufficient earnings and a sense of economic security, they may be compelled to abandon their ancestral trades,” Khirwar said. He ordered the panel’s formation at a meeting on April 10.

However, environmentalist Wangchuk is not optimistic. He says this traditional livelihood will die forever and cites three reasons for its decline -- food subsidies, misplaced education policies and govt’s lack of initiative to develop Pashmina pastures.

Govt policies of 1960s and 1970s providing high food subsidies was the first misstep. “You could get rice in Ladakh village at the price you would pay in Punjab,” Wangchuk said.

While subsidies were phased out in 1990s, their impact has been huge. Wangchuk argued that if the govt had subsidised pastures and goats for the farmers instead, herders could have bought rice if they needed. Subsidies, he said, made them develop a taste for rice -- not a local staple -- and made it easy for them to give up Pashmina rearing.

Wangchuk flagged a “misplaced” education policy next. Under this, children were removed from Pashmina pastures and sent to schools totally disconnected from real life. “They learnt no real-life skills there and the skills they acquired were not useful (in Ladakh),” Wangchuk said, adding they later moved to places like Leh, Jammu and Delhi.

Wangchuk pointed out that there were limited pastures in the area, making it difficult for farmers (Changpas) to keep more goats. Wangchuk said govts in the past could have increased pastures. Instead, solar projects are coming up now, wiping out the few pastures and sounding the death-knell for traditional livelihoods, Wangchuk said.

Professor Feroz Din Sheikh, head of Krishi Vigyan Kendra in Leh, offered a similar assessment. The new generation prefers to move to cities as they see prospects of growth there. Sheikh said the government could help older generations which are still with this age-old practice by providing funds for livestock improvement.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA